Mathieu Braunstein travelled in the Balkans during the 1990's and is the author of the book: François Mitterrand à Sarajevo, le rendez-vous manqué, éd. L'Harmattan, 2001

One week after the horrific terrorist attack in Nice, reading Thomas Hobbes’ “Leviathan” (1651) is disorientating. This English philosopher puts the natural and political body at the centre of his reasoning, and underlines the fact that political forms and gods are mortal. In particular, he clearly states that destroying one’s own life contravenes “natural laws” (chapter 14). Disorder and religion are seen, at least, as an “infirmity” of the state (chapter 29) and the best that can be said of suicide attacks is that they are a poison.

But we won’t be discussing political philosophy at our first encounter with Florent Mehmeti, Artistic Director of Teatri ODA, in Pristina (Kosovo). And we won’t be so insensitive as to quote the Yugoslav author Ivo Andric (1892-1975) and his “Bridge on the Drina” (1945), which summarises the tormented history of the Balkans through a single architectural structure. Florent Mehmeti feels more at ease referring to Ismaïl Kadaré, an Albanian writer whose novel “Who brought Doruntine back?” (or simply “Doruntine” in English), a story of marriage and keeping one’s word, he adapted. Florent Mehmeti was 14 in 1999 when Slobodan Milosevic’s Yugoslavian army forced hundreds of thousands of Kosovars (90% of the population) to leave their homes. For three months, the teenager took refuge with his family to Macedonia, where his father was from. “I ended up being a refugee in my own country”.

"I ended up being a refugee in my own country." Florent Mehmeti

In September 2015, at the first Hapu Festival in Pristina (referencing the two Albanian words “hapësirë” and “publike”, which mean “openness” in Albanian), under the artistic production of Teatri ODA, refugees were a big theme.

The programme included “Hello and Goodbye" (with KunstLabor Graz), a sound and visual installation including the stories of people who have left their homeland; and the “Invisible Walls” performance by Teatri ODA, with its folklore kitsch, distribution of (fake) passports and translucent wall which end up separating groups of spectators. At the second edition of the festival in July 2016, the Franco-Belgian group X/tnt will have set out their “Code of Disconduct for the Schengen zone" for Kosovars who still need visas. And ODA will have evoked the El Dorado of Germany and the mass passage of refugees across the border between Greece and Macedonia in a mosaic piece adapted from indoor theatre.

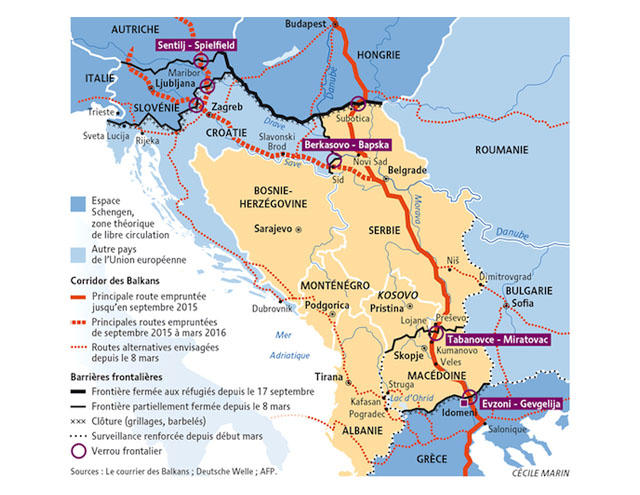

Seventeen years after the war, the small region of the Balkans, whose independence is contested by Serbia and Russia, is located on the edge of the famous Balkans route taken by thousands of refugees on their way to Austria. The situation in the region is still precarious as many decry the controversial expansionist policy further north.

The Balkan Road © Cécile Martin

The Balkan Road © Cécile Martin

Europe, however, seems determined to remember its South-Eastern corner, by naming several Balkan cities as future European Capitals of Culture: Plovdiv (Bulgaria) in 2019; a Croatian city in 2020; and, in a new approach, three cities in the region in 2021 (a Greek city, a Romanian city, and a city representing an EU candidate state, either Herceg Novi in Montenegro or Novi Sad in Serbia)… Will that be enough to strengthen ties?Apart from Doruntine, Ismaïl Kadaré, the great Albanian writer, is also known for another novel, “The Three-Arched Bridge”. But it turns out the allegory doesn’t really work for Pristina. Unusually, the Kosovan capital is not located on a river, and the only bridges it has are for motorways.